Traps are simultaneously one of the most fundamental aspects of D&D style gaming, and also one of the most difficult mechanics to implement within the rest of the game. The two ways it seems to work is either by 1) being so much busywork and rolling as to not matter, or 2) so open ended that they essentially invalidate the very idea of the thief or analogous class.

I have been pondering how to properly run traps for a long time, so many adventures include them and they are such a part of the game's style and feel. Even the real world tomb of Qin Shi Huang had crossbow traps primed to shoot at graverobbers. However, I don't want every trap to be an escalating series of difficulty checks of "I roll to check for traps. I roll to disarm the trap." So in which case, how to do traps?

Now, smarter and better writers than me have already written about this, but on the off chance you find my writing more entertaining or clearer to understand or maybe you just aren't reading any other game blogs, here is my take on the whole traps issue, presented as my Rules Of How To Do Traps Gooder:

Rule 1: Give Clues

I like to be pretty clear with my players that there are two speeds to travel in a dungeon, the first is carefully and the second is pissbolting. I'm assuming that, when traveling through a dungeon at careful speed they are being cautious and checking the floor, and walls, and looking out for anything dangerous. So "You notice a tripwire running across the path" or "That bit of floor looks suspicious".

Maybe I just really hate perception checks for this sort of thing, as simply making the roll/calling for a roll causes a lot of double guessing and meta knowledge, and bogs down the game anyway. I guess the passive perception feature (which I would like to say, one of the great design features of introduced in Fourth Edition D&D) sort of squares this circle, however this sort of cuts off part of the game if you don't have a passive skill high enough. Rather than being something to engage with the trap is just an out of nowhere "fuck you for adventuring" thing.

I think the board-game Heroquest (which is awesome by the way) deals with this well. As long as you have an empty room or corridor you can use your turn to check for traps, and all traps will be revealed to you. It's a sacrifice of action, so traps being hidden has some purpose, however other than that there's no barrier to entry as far as interacting with traps goes. The exception to this is when there are monsters present you cannot search for traps, so running around a room with monsters in it is a trade off between the tactical advantage of closing distance and positioning within the room, and the unknown quantity of any given space.

Pissbolting is, of course, another matter. You don't get to search for sneaky threats to your health and existence whilst running headlong through a corridor being chased by a big awful shoggoth or the like. It's sort of that trade off, like with the example of Heroquest above, where you are taking the risk of traps as a trade off to increased speed away from more certain peril. Also it awards mapmaking and/or marking traps you have found and bypassed.

|

| The perfect trap for players, if not their characters |

Rule 2: Design your traps

So, now your players know there is a trap there in front of them. What do they do now? There is always the possibility that you make disarming the trap a roll, but as I said already I don't really like this as a solution. Either the trap goes off as a fail state (which means you are limited in the range of traps, unless you like lots of "save or die" bullshit), the trap is unsolvable as a fail state (same problems with fail state trigger, with the added downside of effectively walling off parts of your adventure), or leads to dog-piling on the skill check (which is tedious). Trap solving as a unique class ability is also a

I prefer traps as puzzles to overcome or avoid. In order to do this, you need to know how your traps work. You don't need to go all out and design a complete real world working mechanism, but a basic understanding of the trigger mechanism as well as the trap proper.

Once you have an understanding of how you want your trap to work, it leads on to:

The key to a great RPG is player agency, and the key to agency is the free flow of information in order to facilitate meaningful informed choices. Don't willfully obfuscate anything about the trap design that the characters could see, or reasonably be able to puzzle out.

For example, if the first indication that the players can see is that there is something not right about a certain floor tile, they can assume "generic trap" and take steps to avoid that tile entirely as the trigger mechanism. However, they can also look closer and find whether it is a cantilevered floor that will spin out from under unwary feet, or a pressure plate that will trigger some other spring loaded nastiness.

Both traps can be bypassed by leaping over the flagstone in question, however this involves the risk of failing the leap and so another solution must be found. A gangplank could be placed across the cantilevered floor in a way that would not help in the case of the pressure plate. This leads on to:

Rule 4: Roll to Disarm?

Something I don't like being skill checks in terms of traps. Much like the idea of rolling to see what you notice, it just seems to turn all traps into a series of increasing situations to roll dice somewhat arbitrarily. When there is one "disarm traps" roll, it leads to the bifurcating path of the trap going unsolved, or incentivizing dog-piling onto the check.

I'd prefer letting the ingenuity of the players determine how best to deal with the problem before them. If there is a tripwire before them, they could of course step over it, leaving it as a hazard for when they return (or possibly for anything following them), or they could attempt to disarm it by cutting the wire. What if, however, the wire is designed to snap and trigger the trap? This leads back to Rule 3 and letting the players determine the difference between the two types of tripwire if they care to look. If they see holes in the wall, will there be spikes or poisonous snakes that come out of there? Will the trap reset itself or is it a "one and done" hazard?

For this style to work you have to both understand the nature of the trap in a broad sense, as well as be open with the flow of information, being unafraid of giving players the leaps of logic their characters would make in the situation. A character should be able to see if a tripwire is designed to pull a trigger, or snap to release a weight, and both would be countered differently.

Caveat 1: Don't be an asshole

A trap should be a challenge or a trade off, either way there should be a free flow of information. A trap can be a tax on HP for passing though, or a puzzle to be figured, or both, however it is best that the players know what they are signing up for in advance

Also, don't be afraid to make traps easy to solve. They're not the be all and end all of a dungeon, they're supposed to be solved. It's nice to have victories, and lessons learned and implemented can make people feel very clever and accomplished.

Caveat 2: Do be an asshole

Once you have a good grounding of how traps work, that they are puzzles of observation and problem solving, then you can start subverting expectations. This is when you can start pulling out Grimtooth's Traps to start messing with players familiar with traps (it's good to make Kobolds particular terrors for overly arcane and difficult to solve things, playing into the individually weak, collectively strong trope). Trap the trap finders, in fact this is the only situation in which these overly complex things can work. If it's just "roll to find/disarm trap" there's really no difference between a Rube Goldberg machine and a crossbow bolt. It's where the fun and games of this sort of thing is.

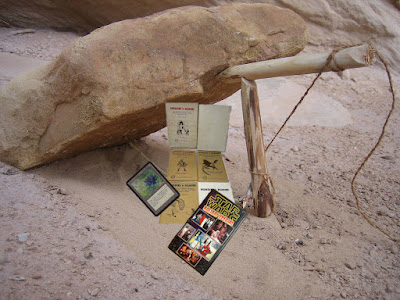

|

| Pictured: The Author hoisted by his own petard |

No comments:

Post a Comment